Water Knowledge

This page provides basic knowledge that is useful for understanding brewing water chemistry. Water is the most basic building block in brewing. Beer can contain up to 97 percent water, so it is by far the largest component in beer. A variety of ions and chemicals can be dissolved in water. Although water is seemingly simple, its ionic components can drastically affect a finished beer’s quality and perception. Those effects may range from dramatic to barely perceptible. The following sections discuss how aspects of water affect the brewing process and the quality and perception of beer.

1. Water Sources

The source of water has a direct affect on its suitability for brewing. Some brewers rely on municipal water supplies for their water while other brewers may have private wells, springs, rain barrels, or other local sources for their brewing water. The water source can also have substantial effect on its quality and variability.

Municipal sources in the United States typically treat and verify that their water is safe to drink. Similar requirements often apply worldwide. Municipal water companies typically rely on surface water sources (rivers, lakes, and reservoirs) and/or groundwater sources (springs and wells) for their water source. A variety of processes can affect the quantity and quality of water from these sources through the year. For instance, large volumes of snow melt or rainfall can provide softer water to a surface water source while that surface water can become more mineralized from groundwater inflow at other times of the year. Additionally, the municipal water source might vary between a variety of surface and groundwater sources as they are consumed through any dry weather periods.

Most municipalities are required to disinfect their drinking water and provide a disinfection residual in their distribution system (piping). Halogenated (typically chlorinated) compounds are frequently used to provide disinfection and a residual of disinfectant in the water lines. If the raw water is unfit for drinking due to hardness or other excessive mineralization, the municipality may treat the water to reduce hardness or mineralization prior to delivering it through their distribution piping.

Differing ionic content of brewing water can affect mashing performance and flavor perceptions in the finished beer. Ions in water come primarily from the soil and rock minerals that the water contacts as it flows through the environment. In areas where the soil and rock are less soluble, the degree of mineralization of the water may be lower. However, when the soil and rock are more soluble, significant concentrations of ions may dissolve into the water. The effect of these dissolved ions on brewing is presented in the following sections.

Wells draw groundwater from underground aquifers. Where these aquifers are isolated from lakes, rivers, marshes, and salt water, their groundwater quality tends to be more consistent (constant) throughout the year. Wells that are not isolated from lakes and rivers may be subject to the same water quality variability of the lake or river. Like surface water sources, the mineralization of groundwater is affected by the type of soil or rock that the groundwater flows through. Groundwater flowing through limestone and gypsum formations typically has more hardness ions than groundwater flowing through granite or sandstone.

Springs provide another source of groundwater. As with the sources listed above, understanding the quality of spring water is still important. The taste and ion content of the water must be suitable for brewing and the water should be free of chemical and microbe contamination. Landfills, waste dumps, and wastewater facilities are examples of facilities that might impact a spring source. A spring water source is not a guarantee that the water is safe to drink or suitable for brewing.

Rivers, lakes, and reservoirs may have additional variability in their water quality due to natural algae and microbes that may create strong taste and odor in water during warmer weather. These taste and odor components can make it past some municipal water treatment methods and leave the water with undesirable taste and aroma that may persist into the finished beer.

When presented with a water source with poor brewing qualities, additional water treatment by the brewer may help correct the water’s faults for brewing usage. Water treatment alternatives such as water distillation, reverse osmosis, carbon filtration, lime softening, water boiling, mineral addition, or acid addition may improve the brewing quality of a water source. Understanding the source of water and its limitations and variability can help maintain the quality and consistency of a brewer’s product.

2. Minerals and Brewing Chemistry

Minerals dissolved in brewing water produce important effects on the overall chemistry of the brewing process. The ions from these minerals alter the water’s pH, Hardness, Alkalinity, Residual Alkalinity, and Mineral Content. These interrelated components are the most important factors in defining the suitability of water for brewing. Adjustments to any one factor can have an effect on the others. Discussion of each factor is presented below.

2.1 pH

pH is a measure of the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution and is related to the concentration of hydrogen (H+) ions in a solution. A very small percentage of water molecules (H2O) naturally split into hydrogen (H+) protons and hydroxyl (OH-) ions. A neutral pH of 7.0 indicates a balanced population of those ions in pure water (at 25°C). Acidic solutions have a pH of between 0 and 7 while Basic solutions have a pH between 7 and 14. The pH of typical municipal water supplies generally lies between 6.5 and 8.5, but may exceed those bounds since pH is not regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act that governs drinking water quality in the U.S. The graphic below illustrates typical water supply and mashing pH ranges.

The pH of the raw water used in brewing has only modest impact on the brewing process. The primary interest to brewing is the pH of the wort during mashing. Factors such as water alkalinity and mash grist composition have greater effect on mashing pH than the starting pH of the raw water.

The pH of the mash influences a number of factors in brewing including; fermentability, color, clarity, and taste of the wort and beer. A slightly acidic mash pH of between 5.2 and 5.8 (measured at room-temperature) improves the enzymatic processes during mashing. The lower end of that range produces more fermentable wort and thinner body. The lower end of that range also produces better extraction efficiency, lighter color, better hot break formation, and the beer is less prone to form haze. Allowing the mash pH to fall below this lower boundary increases the potential to solubilize excess protein into the wort (De Clerck, 1957). The upper end of that range produces less fermentable wort and more body (Briggs et. al., 1981). Tailoring the mash pH helps a brewer create the wort character desired for the finished beer. In most cases, narrowing the target mash pH range to between 5.3 and 5.5 is recommended.

Minor increases in wort or beer pH can create problems in the finished beer. Increased wort and beer pH makes the beer’s bittering perception more ‘coarse’ and less pleasing. The isomerization of alpha acids during the boil increases slightly as wort pH increases, which may add to the coarseness. Another problem is that increased pH in wort and the finished beer slows the reduction and removal of diacetyl from beer during maturation. During mashing, a pH greater than 6.0 can leach harsh-tasting silicates, tannins, and polyphenols from the grain into the wort (Briggs et. al., 1981). Reducing sparging water pH to between 5.5 and 6.0 can help avoid a rise in mashing pH during sparging.

Mash pH measurements vary with the temperature of the mash. There are two components to this pH measurement variation. The first component is a chemical change caused by the change in the energy in the water that makes it easier to split hydrogen protons from acidic molecules in the mash. A hotter mash is therefore a bit more acidic. The second component is due to the change in electrical response of the pH meter probe electrodes with temperature. These two factors produce a mash pH measurement (when using a pH meter) that measures about 0.2 to 0.3 units lower at 150°F than at room temperature. Therefore, it is important to standardize the temperature at which mash pH is measured. All pH readings presented on this page assume measurement at room-temperature [between 20°C and 25°C (68°F to 77°F)].

Brewers should note that Automatic Temperature Compensating (ATC) pH meters only compensate for the response of the pH meter's electrode at varying temperature. That feature does not compensate for the actual pH shift produced chemically in the mash as mentioned above. All mash pH measurement should be performed at room-temperature. Another consideration is that most pH probes use a thin glass bulb that will be subjected to more thermal stress when inserted into a hot mash and the probe is more likely to fail prematurely. Therefore, ATC-equipped pH meters are not necessary for brewing use since it is important to cool the sample to room temperature to avoid the chemical mash pH variation and damage to the pH probe.

SPECIAL NOTE: pH meters require calibration between uses or at regular intervals to verify their measurement accuracy. Meter calibration using pH 4 and pH 7 reference solutions is recommended. Those solutions have limited shelf life and should be replaced within a year after opening. Refrigerating the reference solutions may improve their shelf life, but the solutions should be warmed to their reference temperature (typically 20°C to 25°C) prior to calibration use. The glass electrode used in many pH probes is often filled with a potassium chloride solution. The pH probe should be stored in a similar potassium solution (storage solution) to improve the probe’s lifespan. Do not allow the probe bulb to 'dry out' since this can shorten its lifespan. Some probe's include a air-tight cap that is fitted over the probe end to help keep the bulb moist. A drop or two of water in the cap can help avoid dry out. A pH meter with a resolution of 0.05 standard units or better is helpful in assessing when a pH reading has stabilized and that reading can be recorded. Avoid meters that can only report to 0.1 units.

SPECIAL NOTE: Plastic pH strips (ColorpHast-trade name) typically used by brewers are reported to miss-report mash pH by about 0.2 to 0.3 units lower than actual. Brewers should use caution when using pH strips to measure mash pH. Without another means of pH verification, brewers are advised to accept a pH strip reading that is about 0.2 units below their targeted mash pH to avoid overshooting the pH. A pH strip reading of about 5.0 to 5.2 should indicate an appropriate room-temperature mash pH of around 5.3 to 5.5. pH measurement by a calibrated pH meter is recommended. Since pH strips function based on their interaction with the ionic content of the solution, the relatively low ionic strength of typical brewing water does not produce a rapid response by pH strips. Leaving the strip submerged for at least a minute in the cooled wort is recommended by the manufacturer of the ColorpHast strips. Common paper pH strips are not recommended for brewery use since they are reported to have less reliability and accuracy than plastic pH strips.

SPECIAL NOTE: Five Star 5.2 Stabilizer is indicated by its manufacturer to "lock in your mash and kettle water at a pH of 5.2 regardless of the starting pH of your water". Evidence by homebrewers indicates that this product does not produce a mash pH in the preferred room-temperature range of 5.3 to 5.5. That evidence shows this product does produce some pH moderation in waters with high Residual Alkalinity. However, the mash pH tends to center around 5.8 (room-temperature measurement). While 5.8 pH is acceptable, it is at the upper end of the desirable mashing range. The evidence also shows that in waters with low Residual Alkalinity, this product shows little effect on mash pH. Since Five Star 5.2 Stabilizer is a compound with high sodium content, its use will elevate the sodium concentration in the brewing water. High sodium content can be undesirable from a taste standpoint in beer. Proper alkalinity control of mashing and sparging water may produce more acceptable brewing results for most brewers than with the use of 5.2 Stabilizer. To add emphasis to difficulty in using this product, the following conversation posted on Homebrew Talk between noted brewing water expert, AJ DeLange and the chemist from Five Star Chemical regarding their 5.2 Stabilizer product. "Tipped a few last night with the chemist who designed this product and was able to confirm that it is indeed a mix of phosphates (mono and di basic) that accounts for the presence of the malt phosphate. This is something I have long suspected and am pleased to have finally confirmed. Good manners prevented me from pressing him on it's efficacy and suitability relative to the statement on the label. But his comments on it were basically that most brewers shouldn't use it/need it and that it was put together for a particular brewery that had variable source water and no desire to make any effort to track that variability."

2.2 Hardness

Hardness in drinking water is primarily due to its calcium and magnesium content. High concentration of calcium or magnesium ions produces hard water and low concentration of those ions provides soft water.

A common misperception among brewers is that hardness in brewing water is not desirable. That is not true. A more valid way to consider brewing water suitability is summarized below.

Hardness is Good

Alkalinity is Bad

The hardness or softness of water does not indicate its suitability for brewing. As illustrated in the sections below, both very soft water and very hard water can be utilized for brewing as long as the appropriate alkalinity is provided for mashing. Since there is often a minimum calcium content desired in brewing water, moderately hard to hard water may be desirable for brewing. In some cases, soft water may be desirable for brewing some beer styles. Although the statement above indicates alkalinity is bad, an appropriate level of alkalinity is desirable in brewing water. The problem is that water supplies often have higher alkalinity than desirable for brewing. High alkalinity may lead to higher than desired mashing pH.

Water hardness varies regionally and by source. The map below illustrates how hardness varies in surface waters across the United States (Briggs, 1977). Much of the Western and Midwestern U.S. often has high hardness while coastal or mountainous regions may have lower hardness. Groundwater hardness may or may not mimic the surface water hardness shown below, but drinking water aquifers tend to cover regional areas and can have more consistent water quality.

Water Hardness can be either Temporary or Permanent. These forms of hardness are discussed below.

Temporary Hardness results when calcium or magnesium are paired with carbonate and bicarbonate in the water. Temporary Hardness can be reduced by boiling treatment and by treatment through lime softening.

Permanent Hardness results when calcium or magnesium are paired with anions such as chloride and sulfate that cannot be driven off by boiling the water. Enhanced softening processes are required to reduce permanent hardness in water. Distillation, deionization, and reverse osmosis (RO) processes are examples of enhanced softening processes.

Total Hardness is the sum of Temporary Hardness and Permanent Hardness in the water.

Hardness is often reported in terms such as “as CaCO3”. The “as CaCO3” term is also used to report water alkalinity and it is important to differentiate those water characteristics even though they use similar reporting terms.

2.3 Alkalinity

Alkalinity is a measure of the "buffering" capacity of a aqueous solution and its ability to neutralize strong acid and resist pH change. Alkalinity is defined as the amount of strong acid required to lower the pH of a sample of the water to a specified pH (typically 4.3 to 4.5). Alkalinity is generally due to the concentration of carbonate (CO3), bicarbonate (HCO3), and hydroxyl (OH-) ions in water. Higher alkalinity water requires more acid to change the water’s pH. In typical drinking water, alkalinity is directly related to the concentration of bicarbonate in the water. Alkalinity is often reported using terms such as “as CaCO3” and care must be used to avoid confusing it with similar hardness results.

Like hardness, alkalinity tends to vary on a regional basis. The map below illustrates how alkalinity varies across the United States (Omernik & Powers, 1983). As indicated by the map, much of the U.S. has relatively high alkalinity in surface waters. Of the regions with reduced alkalinity, many are mountainous or are regions without carbonate rock near surface. Carbonate rock and soils impart alkalinity to water.

Alkalinity has a significant effect on beer flavor. Excessive alkalinity can cause wort and beer pH to be higher than desired and beer flavor can suffer. High wort and beer pH can create 'dull' flavors, harsh bitterness, and darker beer color. Conversely, when alkalinity is too low, wort and beer pH can be too low, which can reduce beer body and affect beer flavor.

Beer perception differs significantly from wine in large part due to the difference in alkalinity between beer wort and grape must. The flavor of wine can be characterized as a balance of sweet and sour while most beers can be characterized as a balance of bitter and sweet. The acidity of wine provides most of the balance to the wine sweetness while the bittering from hops provides most of the balance to the beer sweetness. The alkalinity of grape must (juice) is typically negative due to its pH being under 4.3. After fermentation, wine pH typically falls into the 3 to 3.5 range. The alkalinity of beer wort helps keep the pH of beer in the 4 to 4.5 range and helps avoid the wine-like reliance on acidity for flavor balance.

Even when brewed with very low alkalinity water, beer wort is typically buffered by compounds in the malt grist to produce a wort pH in the mid to low 5 range. Brewers should avoid over acidifying wort which can create tart or wine-like character in their beer. The effect of alkalinity on brewing can be aided through the concept of Residual Alkalinity.

2.4 Residual Alkalinity

Residual Alkalinity (RA) is brewing-specific value that is derived from both the water's Hardness and Alkalinity to help evaluate potential mashing pH conditions. RA was described in the 1940’s by Paul Kohlbach. He showed that during mashing, calcium and magnesium in the brewing water react with phosphatic compounds (phytins) in the malt to produce acids that neutralize the brewing water’s alkalinity. The water’s alkalinity is effectively reduced by its hardness. This interaction between the brewing water’s hardness and alkalinity is expressed by RA.

RA is an indicator that is specific to brewing and is a factor in defining the suitability of water for brewing. RA is estimated with the following equation when calcium, magnesium, and alkalinity are input as (meq/L) or (ppm as CaCO3). The equation below assumes the use of ppm “as CaCO3”.

With RA, a brewer can better understand the interplay of alkalinity and water hardness and its effect on mashing chemistry and performance. A simplified chart depicting Alkalinity, Hardness, and RA is presented below. Lines of constant RA cross the chart diagonally. This chart is based on work by A.J. Delange.

RA can be adjusted by either hardness adjustment or alkalinity adjustment as illustrated in the chart above. For instance, Burtonizing the brewing water by adding Gypsum and/or Epsom Salt is an example of reducing RA by increasing the water hardness. Adding acid to the water is an example of reducing RA by reducing alkalinity. Decarbonating water by boiling can be used to reduce RA in water with high Temporary Hardness since that process reduces alkalinity. Adding Chalk, Pickling Lime, or Baking Soda are examples of increasing RA by increasing alkalinity. Diluting water with distilled or RO water brings the RA of the diluted water closer to zero.

RA provides a rough indicator of where the mash pH will end up and if there is a need for water chemistry adjustment. Although the RA Chart suggests that beer color influences what RA value is appropriate for a beer, the relationship is more complicated than that. The acidity provided by various grain types is not proportional to the color they impart to the beer. Therefore, a direct relationship between beer color and RA is not possible. However, correlations with grain acidity do help assess the RA needed in mashing liquor to produce desirable wort pH. A discussion of grain acidity and its variation, is presented below.

Grain Acidity

The various grains used in brewing can be generally divided into four categories: Base malt, Crystal malt, Roast malt, and Acid malt. Each category has different acid content characteristics.

Base malts are malts and grains that have not been stewed to produce sugars in the malt or grain kernel and have relatively low color rating (<20 Lovibond (<52 EBC)). Flaked malt and grain should be considered base malts.

Crystal malts have been stewed in the kernel to produce sugars in the malt and can have color ratings from about 1 to less than 200 Lovibond (~530 EBC).

Roast grains are malts or grains that are roasted to a color rating of greater than 200 Lovibond (~530 EBC).

Acid malts are low color malts that are infused with 2 to 3 percent lactic acid for mash pH reduction purposes.

The acid content for the Roast and Acid malts is somewhat consistent within those categories and their acid content does not vary significantly with malt color variation. However, the acidity of either Roast or Acid malts can vary due to manufacturer or production methods. For Base and Crystal malts, their acid content does tend to vary with their color rating (Lovibond or EBC). The table below describes the general variation of acid content for the grain categories. The grain acid content information was taken from research performed by Kai Troester, 2009. Be aware that there are grains and malts that do not conform well with the acid content relationships presented below. Predicting mashing pH with these relationships is still not precise for that reason.

Even though a direct and accurate relationship cannot be made between beer color and RA, a general relationship is apparent. Lighter color beers benefit from lower RA and darker color beers benefit from higher RA. As the acid content of the mash’s grain bill increases, the mashing water RA must also rise proportionally to maintain the mash pH.

The success in brewing pale beer in Pilsen is due to the soft and low alkalinity water found there (RA is near 0). Likewise, the success of brewing pale beer in Burton-on-Trent is due to the very high hardness and high alkalinity that still produce low RA. Low RA waters are well-suited to brewing pale beers since the mash pH is more likely to fall into the desired pH range. Low RA waters are less suitable for brewing dark beers since the acidic dark grains can drive the wort pH lower than desirable, which reduces the effectiveness of mash enzymes and possibly produces a sharp, acidic, or tart beer.

The success in brewing dark beers in places such as Dublin, Edinburgh, Munich, and London that have higher Residual Alkalinity water (RA greater than 50), is due to the more acidic dark grain used in their grist. The elevated water alkalinity and resulting RA, moderates the increased acid content of the dark grain to produce smoother dark beers brewed in those locations. That raised the reputation of those locations for brewing fine dark beer styles. Without the additional dark grain acid content to neutralize the high alkalinity, the mash pH of a pale grist would not drop into the desired range for good enzyme performance and the resulting beer might present a harsh character because of the leaching of silicates, tannins, and polyphenols into the wort during mashing. High quality, light-colored beers are more difficult to produce in these locations if the alkalinity of the brewing water is not reduced. To brew light-colored beers using water with elevated alkalinity, an external acid addition is required. Either an acid rest, acid malt, or liquid acid is required to neutralize elevated water alkalinity when brewing lighter-colored beers.

Coordinating the acid content of the malt bill and the alkalinity of the water is important for conducting a mash that produces a pH in the optimum range between 5.2 and 5.8. The enzymatic processes in the mash are hindered when the mash pH falls outside that range. Enzymatic activity varies with pH and temperature as illustrated in the following graphic by Palmer (1999).

It’s notable from the graphic that the various enzymes work well across a range of pH. Therefore, targeting an exact mash pH is not critical to success. Achieving a mash pH that is within a tenth or two of the desired target can produce acceptable results. General suggestions for mashing pH targets are provided in the table below. As can be seen in the table, mashing pH has multiple impacts and the brewer can tailor the pH to enhance certain goals. Be aware that other factors beyond pH can affect character. The pH only helps achieve that character.

2.5 Mineral Content

Dissolved minerals (ions) are typically present in all natural waters, although rainwater may have very low ion concentrations. The type and concentration of those dissolved minerals can have a profound effect on the suitability of water for brewing use, its mashing performance, and the flavor perception of beer. A discussion of dissolved minerals that are a concern to brewers is presented below. Mineral salts create ions when they dissolve in water. These ions are either positively-charged (Cations) or negatively-charged (Anions).

2.5.1 Undesirable Ions

The first consideration is that brewing water should have high quality and be safe to drink. This requires that the water have no pollutants and have little or no iron, manganese, nitrites, nitrates, or sulfides. Organic pollutants and chemical contamination have no place in beer. The following ions are commonly found in water supplies, but their concentrations must be low in order to not affect the finished beer.

Iron may be tasted in water at concentrations of greater than 0.3 parts per million (ppm or mg/L) which may also be reported as 300 parts per billion (ppb or µg/L). Iron has a very metallic taste that is easily conveyed into the finished beer. Popular guidance says that the iron content of brewing water should be below 0.1 ppm to avoid tasting it in beer. Rust-colored deposits on plumbing fixtures may be an indicator of elevated iron content in water. Even in the absence of metallic flavor, iron in brewing water can produce a Fenton reaction that can oxidize beer and reduce its life.

Manganese may be tasted at concentrations of greater than 0.05 ppm or 50 ppb. Manganese has a very metallic taste that is easily conveyed into the finished beer. Black-colored deposits on plumbing fixtures may be an indicator of elevated manganese content in water.

Nitrate is not a great concern in brewing, but should generally be less than 44 ppm in the water source to protect infants that may drink the water. Nitrate concentrations may also be reported in the form, Nitrate as Nitrogen (NO3-N). 44 ppm nitrate is equivalent to 10 ppm nitrate as nitrogen. Children and adults can tolerate higher nitrate concentration and the 44 ppm limit may not be a concern in brewing. However, nitrate in brewing water should reportedly be less than 25 ppm (De Clerck, 1957). High nitrate concentration in the water may be converted to nitrite in the mash and nitrite becomes poisonous to yeast at levels above 0.1 ppm. If elevated nitrate levels are found in water, associated ions such as nitrite and ammonia should also be tested for.

Sulfide compounds that might be exhibited as sulfur or rotten-egg aromas should not be perceptible in the water.

2.5.2 Major Ions in brewing

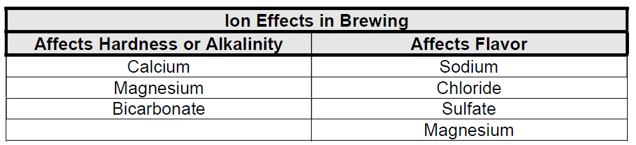

The major ions of interest to brewers are shown in the table below. These ions have the greatest effect on the quality and perception of finished beer.

These ions can also be grouped in another way. Calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate produce hardness and alkalinity that affect the mash pH. Sodium, chloride, sulfate, and magnesium ions affect flavor, which adds important nuances to beer perception.

A discussion of the effect of each of the ions is presented below.

Calcium is typically the principal ion creating hardness in water. It is beneficial for mashing and enzyme action and is essential for yeast cell composition. Typical wort produced with wheat or barley contains more than enough calcium for yeast health. In the mash, calcium reacts with the malt phosphates (phytins) to lower the mash pH by precipitating calcium phosphate and liberating protons (H+). Calcium improves the flocculation of trub and yeast and limits the extraction of grain husk astringency. It also reduces haze and gushing potential, improves wort runoff from the lauter tun, and improves hop flavors. The ideal range for calcium ion concentration in ales may be 50 to 100 ppm although exceeding this range may cause phosphorus (an essential yeast nutrient) to precipitate excessively out of solution.

Oxalates are natural component of brewing grains. Since oxalates are precipitated through complexing with ionic calcium, insufficient calcium in brewing water may leave excess oxalate in the wort which can contribute to beerstone (calcium oxalate) formation. A minimum concentration of 40 ppm calcium is recommended to reduce beerstone formation potential. Calcium concentration of less than 40 ppm can be tolerated in brewing water for beers that benefit from less mineralization (ie. pilsners and light lagers) with the understanding that additional measures may be needed to ensure adequate beer clarification, and beerstone removal.

Brewing with very low calcium content water does not impair fermentation since barley and wheat provide sufficient calcium for yeast health. The primary difficulties with brewing with very low calcium water is that yeast flocculation may be impaired and beerstone formation may affect equipment. Both of these problems can be alleviated through practices such as lagering, filtering, and active maintenance for beerstone removal. The calcium content of brewing water should generally conform to the calcium content that the original yeast evolved to. Therefore, an English ale yeast might expect high calcium content water while a Czech lager yeast might expect very low calcium content. (Brungard, 2015)

Another consideration is that the calcium content for brewing water may be tailored to increase or decrease yeast flocculation. For example, if a yeast is known to drop out prematurely, then reducing calcium content could be employed to reduce that tendency. For most lager brewing, low calcium content water is more likely to produce better results. Brewing water with low or no calcium content can be OK for Lagers.

Increasing the calcium content of mash water is a useful tool for reducing the pH of the mash water. Calcium content has little effect on beer flavor but it is paired with anions that may increase the minerally flavor of the water when present at elevated concentrations. A problem with high calcium content brewing water is that the calcium displaces magnesium from yeast and that can have a negative effect on yeast performance. Avoid excessive calcium content when yeast performance is below expectations. (Note: adding calcium to sparging water does not reduce the water’s pH or alkalinity since there are few malt phytins present to complete that reaction. An acid must be used to reduce the alkalinity and pH of sparging water.)

Magnesium is typically the secondary ion creating hardness in water. It accentuates flavor with a sour bitterness when present at low concentration, but it is astringent at high concentration. Magnesium is a yeast nutrient and an important co-factor for certain enzymes. Like calcium, magnesium reacts with the malt to lower the mash pH, but with a reduced effect compared to calcium. The preferred range for magnesium concentration is 0 to 30 ppm. Exceeding 40 ppm is not recommended. A minimum of 5 ppm magnesium is known to be desirable for good yeast flocculation, however a typical barley or wheat mash grist will contribute more than 5 ppm magnesium to the wort for proper yeast flocculation and it is not necessary to add magnesium to brewing water unless it is desired for its flavor effects. Increasing the magnesium content of mash water is not a useful tool for reducing the pH of the mash water since the allowable concentration range for magnesium is small.

Sodium – The sour, salty taste of sodium accentuates beer's flavor when present at modest concentration. It is poisonous to yeast and harsh tasting at excessive concentrations. It accentuates flavor when used with chloride and imparts roundness to the beer flavor. The preferred sodium concentration range is 0 to 150 ppm, but the upper limit should be reduced in water with high sulfate concentration to avoid harshness. A practical maximum concentration of 100 ppm is recommended for brewing, but brewers should recognize that waters from the historic world brewing centers have less than 60 ppm sodium. Keeping sodium concentration below 60 ppm is therefore recommended in practice. Most tasters find that “salty” flavor becomes apparent in drinking water when its sodium content exceeds 250 ppm. While low sodium is desirable, some beer styles such as Gose may have much higher sodium concentration (~250 ppm) as part of their desired flavor profile, but that sodium is typically added to the post-fermented beer.

Chloride – Chloride accentuates fullness and sweetness and improves beer stability and clarity. The ideal range is 10 to 100 ppm, but the upper limit should be reduced in water with high sulfate concentration to avoid harshness or minerally flavor. When brewing with sulfate concentration of over 100 ppm, limiting the chloride content to around 50 ppm is recommended. The minerally flavor of Dortmunder Export may be due to the typical 130 ppm chloride concentration along with the 300+ ppm sulfate content in Dortmund’s water. Brewers of juicy IPAs have reported that brewing liquor with around 150 ppm chloride and 75 ppm sulfate provides fullness without lingering too long on the palate. Chloride does not make beer maltier, it helps any malt in the beer to be perceived more readily.

Be aware that the chloride ion is not the same as the disinfectant, chlorine and should not be confused with it.

Sulfate – Sulfate provides a sharper, dryer edge to highly hopped beers. The ideal concentration range is 0 to 350 ppm, although the concentration should typically not exceed 150 ppm unless the beer is highly hopped. Sulfate concentration above 350 ppm has been reported to produce sulfury aroma in finished beer. The use of the historic Burton water profile (sulfate greater than 600 ppm) may not produce ideal ales for that reason.

Including some sulfate in brewing water can help dry the finish and avoid an overly full or cloying finish, even in malty beer styles. Sulfate does not make beer bitter, it helps any bittering in the beer to be perceived more readily. Brewers should recognize that high sulfate level in brewing water along with either high sodium or chloride levels can produce harsh or minerally flavor in beer.

Bicarbonate – Bicarbonate is a strongly alkaline buffer that is typically responsible for the alkalinity in most drinking water. Malt acids produced during mashing do consume some of the bicarbonate in the brewing water. When there aren't enough malt acids to neutralize the brewing water's bicarbonate content, the mash pH may not fall into a desirable range, which may reduce enzyme action and make hop flavors more harsh. When brewing lighter colored beers, bicarbonate is generally undesirable in brewing water and is best kept below 50 ppm or should be balanced with additional calcium to reduce the Residual Alkalinity of the brewing water. When brewing darker colored beers, some bicarbonate may be needed in the mash water to balance the higher acidity provided by the dark-colored grains. High bicarbonate concentration and its resulting alkalinity is not desirable in sparging water due to the increased potential to leach harsh-tasting silicates, tannins, and polyphenols into the wort. The potential to leach these compounds from the grain increases as the remaining wort’s specific gravity falls during sparging. Control and adjustment of bicarbonate in brewing liquor is an important factor in producing a desirable mash pH and subsequent wort pH in the kettle.

Alkalinity can be approximated from bicarbonate concentration (or vice versa) if the water pH is less than 8.5. That assumption is valid for many natural water supplies. The equation below provides that approximation.

2.5.3 Acids

Acids can be an important component in brewing water adjustment. Acids come in solid and liquid forms and all add hydrogen protons (H+) to the water and move the pH of a solution lower. Acids also add their unique anion to the water. Frequently, the anions have distinctive flavor that may compliment or degrade beer flavor when they are present in beer at levels above their taste threshold. Some acids are more perceptible in beer than others.

Phosphoric acid is more difficult to perceive in beer since beer contains similar phosphatic compounds. It is typically the most flavor-neutral acid used in brewing and the various phosphate anions remain relatively undetected to most tasters at under 1,000 ppm.

Hydrochloric and Sulfuric acids can add chloride or sulfate ions that may be desirable in the flavor profile. The contributions and limits for those ions are discussed in the section above.

Citric, Malic, and Tartaric acids can add fruity or estery perceptions to the beer. The typical anion taste thresholds for most tasters are: (Citrate = 150)(Malate = 100)(Tartarate = 600) ppm.

Lactic and Acetic acids can impart their unique flavor to beer. Lactic is smooth while Acetic is pungent. The typical anion taste thresholds for most tasters are: (Lactate = 400)(Acetate = 175) ppm.

2.5.4 Minor Ions

There are minor ions in water and wort that can effect fermentation and flavor. Undesirable ions were highlighted at the beginning of this section. Minor ions can have a beneficial or detrimental effect depending on their concentration.

Potassium – Potassium is a component of malt and it is contributed to wort. The ionic potassium content of water has some effect on flavor, adding a ‘saltiness’ to the beer at elevated concentration (typical taste threshold around 100 ppm). Potassium in the water at levels above 10 ppm are reported to inhibit certain enzymes. Since potassium is contributed by the malt, there is little need to add more to brewing water. Potassium carbonate is popular in winemaking due to its ability to precipitate tartaric acid and neutralize excess acidity. However, typical beer wort does not have significant tartaric acid and its use in brewing is less appealing.

Zinc – Zinc is a yeast nutrient when present at very low concentrations of 0.1 to 0.2 ppm and that level should not exceed 0.5 ppm in wort. Zinc is present in malt and zinc extraction is improved with lower mash pH. When present at higher levels (>1 ppm), zinc becomes toxic to yeast and produces a metallic flavor. Commercial yeast nutrient preparations typically provide zinc in their formulation. Zinc chloride or zinc sulfate may be used to produce the desired zinc concentration in wort. However, the dosing of those zinc salts is very low. For example, the dose of solid zinc sulfate heptahydrate is 1 gram per 10 barrels of ale or 1 gram per 20 barrels of lager.

Reverse Osmosis water treatment reduces zinc content in RO water to extremely low concentrations. Brewing with either RO or distilled water (or any natural water with less than 0.1 ppm zinc) should include zinc supplementation.

Copper – Copper is a beneficial complexing agent at low concentration (~0.1 ppm) in wort. Sulfides and other sulfurous compounds can be complexed out of the wort by copper. The copper concentration should be kept below 1 ppm to avoid mutagenic effects to yeast and metallic flavor. Historic brewing practices often used all copper boil kettles, so it appears unlikely that overdosing wort from copper contact will occur. A modest area of exposed copper metal in contact with the wort during the brewing process is typically sufficient to provide beneficial copper contribution. For instance, a couple of inches of copper tubing in a 5-gallon (19L) batch may be sufficient to produce a beneficial copper concentration in wort. The tubing is placed in the kettle during the boil and reused repeatedly. If the brewing equipment or water supply piping already includes copper tubing or surface area within the system, then adding the piece of copper to the boil kettle may be unnecessary. Brewers should be aware that excessive copper ion in brewing water does increase the possibility of oxidizing (Fenton) reactions that can accelerate the oxidation and staling of finished beer. Keeping copper content low (but not too low) in brewing water and wort should improve the longevity of beer.

3. Minerals and Beer Styles

The historic beer styles that have developed around the world were sometimes the result of the water conditions present in that area. Prior to the understanding, measurement, and ability to adjust water chemistry, beer styles evolved to suit the local water. Typically, dark-colored beer styles developed in areas with high RA water and light-colored beer styles developed in areas with low RA water.

Additionally, ions affecting beer flavor perception in the local water also influenced beer styles. For instance, malty styles may be enhanced in areas with low sulfate concentrations while hoppy styles were enhanced in areas with elevated sulfate concentrations.

Examples of the ionic concentrations of water from various major brewing centers are shown in the table below. There are a variety of literary sources that provide differing estimates of the appropriate ionic concentrations for these brewing waters. For some of those literary sources, the quoted ionic concentrations are known to be incorrect since the indicated ionic balance could not exist at reasonable pH levels and the water profiles are not supported with factual laboratory data. The concentrations shown in the table below have been researched and verified with historic and current references. The profiles are also corrected where necessary to provide an appropriate ionic balance. The RA calculated for each of water profile is provided in the table for reference.

Although the historic water profiles presented above are reasonably accurate representations, it does not mean that the brewers from those areas used these waters without treatment prior to brewing.

Burton The groundwater in Burton-on-Trent is the result of upwelling from the Mercia Mudstone (a gypsum-bearing formation) into the surficial Sand and Gravel aquifer where it mixes with groundwater supplied by rainfall infiltration and the nearby Trent River. The more the brewers of the region utilized the shallow water source, the more the sulfate-laden upwelling was diluted by the rainwater and river water. The amount of rainfall and the river level affected their local groundwater quality.

The location of the water supply well also has an influence in Burton. At Marston Brewery, the sulfate content of their groundwater is up to 800 ppm. While at Coors Brewery, the sulfate content of their groundwater was only about 200 ppm. These were sampled at the same time and the samples come from the same Sand and Gravel aquifer (Pearson, 2010). Therefore, defining a “true” Burton water profile is not possible. Research on the physical setting in Burton suggest that the high sulfate groundwater was diluted by inflow from the nearby River Trent and breweries did not brew with the high sulfate concentration shown in the table above. (Brungard, 2014).

The balanced Burton water profile shown above was estimated based on the relative concentrations of ions observed from the Sand and Gravel aquifer, but those concentrations could be higher or lower depending upon time of year and location. At over 600 ppm sulfate, the profile provided is not as mineralized as that groundwater resource gets, but it is highly mineralized. Brewing with the Burton profile may be extreme and may produce sulfury notes in the finished beer. An alternative would be to brew with the Pale Ale profile that is included in Bru'n Water as a first try for brewing a hoppy beer (300 ppm sulfate).

Dortmund The local groundwater in Dortmund is very hard and mineralized. The high hardness reduces RA and made it possible to brew pale beers with a minerally edge. Due to the mineralization, water is now piped in far from Dortmund. The profile presented for Dortmund does produce a substantially minerally-tasting beer and brewers may want to moderate the sulfate and chloride content in practice.

Dublin Water quality in Dublin is highly dependent upon location within the city. In the north and west parts of the city, drinking water is hard and alkaline from the River Liffey. But south of Dublin, water comes from the Wicklow Mountains where the water is only lightly mineralized. Interestingly, Guinness’ St James Gate brewery was traditionally fed from the Wicklow Mountains and the tart character of their dry stout was developed with that water and not the hard, alkaline water found in the rest of Dublin. While more alkaline water is typically used in stout and porter brewing, dry stouts are more authentic when brewed with Wicklow water which can be similar to RO water. (Brungard, 2013)

Edinburgh As with many breweries, their water source was taken from the area immediately around the brewery. In the case of many Edinburgh breweries, the groundwater was somewhat hard and mineralized. Somewhat elevated sulfate content was typical and that helped malty beers from the area to present a pleasingly dry finish to that maltiness. Modern Edinburgh has outgrown the local water supply and water is now piped in from miles away.

London This is actually a tale of two cities, or more accurately, two water sources. The original water source for London was River Thames. It’s moderate hardness and alkalinity made it feasible to brew pale beers with it. Some say the original pale ales and IPAs were developed with that water. London’s real fame came from Porter brewing and that had to due to the advent of well drilling and the presence of soft, slightly salty, and alkaline groundwater below the city. The water has significant sodium, sulfate, and chloride. That water was suited for Porter brewing. While the Thames is still a source of London water, the groundwater below the city is now rarely used for brewing use due to pollution. (Brungard, 2014)

Munich All of southern Bavaria has similar geology and water quality. The limestone beneath Bavaria provides a hard and alkaline groundwater that is otherwise low in flavor ions such as sodium, sulfate, and chloride. The high alkalinity and hardness of that raw water are somewhat suited to brewing the dark styles originally produced in the city, but it was difficult to produce the lighter colored beers that the city became known for. Brewers developed forms of alkalinity reduction to make their water suitable for pale beers. (Brungard, 2014)

Vienna Groundwater from wells along the Danube River supply the city. With Vienna being downstream of Bavaria, the water quality somewhat mirrors the quality of Munich and that region.

Pilsen Located in an area with little limestone or dolomite contact, the surface water and groundwater tends to have little mineralization. While the raw water has low mineralization, its reported that breweries such as Pilsner Urquell add a small amount of gypsum to their brewing liquor.

As mentioned above, the brewers in those historic locations may have further treated their local water to make it more suited to their brewing. Of particular interest is the use of decarbonation to soften the water by boiling. Another treatment option was to use saurermalt (acidified malt) or saurergut (soured wort) to reduce water alkalinity. Decarbonation by Boiling and Lime Softening are discussed in the Alkalinity section below. A selection of estimated “boiled” water profiles is provided in that section to illustrate the difference that boiling can create in the water profiles.

4. Water Treatment

No single water resource can provide ideal conditions or results for brewing all beer styles. At best, a water source may be suited to brewing a limited range of beers without additional treatment. Water treatment may be needed for a number of reasons including:

Chlorine Removal

Hardness Adjustment

Alkalinity Adjustment

Mineral Profile Adjustment

4.1 Chlorine Removal

Chlorine is typically found in municipal water supplies to assure the water’s disinfection from disease-causing organisms. The typical chlorine residual in drinking water is around 2 to 3 milligrams per liter (or ppm). However, higher dosing may be present when problems with the water piping system occur. Chlorine removal from brewing water is critical for good brewing results. Although the term chlorine is used generically here, hypochlorite, chloramines, chlorine dioxide, and bromine are other disinfection agents used in municipal water disinfection. In water, chlorine gas dissociates to form hypochlorite ion (OCl-). If ammonia is added to that chlorinated water, chloramines are formed. That process can produce mono-, di-, or tri-chloramine depending upon the ratio of chemicals used. Municipalities increasingly use chloramines for disinfection since that compound is more stable than hypochlorite and can form fewer undesirable by-products in the water.

If chlorine compounds are not removed from brewing water, they combine with the organic compounds naturally found in wort to form chlorophenols. Chlorophenols can be detected in beer at concentrations as low as 10 parts per billion (ppb) and they have a distinctive medicinal, band-aid flavor that is objectionable in both flavor and aroma. They are plainly detectable in beer at over 30 ppb. Unfortunately, not all tasters can detect chlorophenols at low level and some tasters may regard them as non-objectionable as found in some Scotch Whiskys. As noted above, typical tap water has about 100 times the concentration of chlorine compounds needed to produce chlorophenols. Untreated municipal tap water can be expected to produce those objectionable effects if not thoroughly removed from brewing water.

The use of bleach as a sanitizing agent in the brewery can leave chlorine compounds on brewing equipment and in brewing water. Other sanitizers such as iodophor and acid-based cleaners can be more effective, produce fewer off flavors, and require no rinsing. Switching from bleach to these sanitizers can produce a substantial improvement in the quality of a finished beer by avoiding chlorophenol production. If bleach is used as a brewery sanitizer, all equipment that touches water, wort, or beer should be thoroughly dried prior to contact. Be aware that iodophor can also produce a minor phenolic off-flavor if that sanitizer is not removed from equipment.

Several options are available for removing chlorine from brewing water:

Boiling

Aeration

Metabisulfite addition

Ascorbic Acid addition

Activated Carbon filtration

4.1.1 Boiling

Boiling is effective for hypochlorite removal, but requires time and energy to perform the boil. While hypochlorite is volatile and can be boiled off, boiling is less effective for chloramines removal. Hours of boiling time are required to remove chloramines and the cost effectiveness of that treatment method is poor. Boiling could be a good choice when the water supply has high temporary hardness and hypochlorite disinfection since it can help both problems. Review the section below on Decarbonation by Boiling.

4.1.2 Aeration

Aerating tap water can be used to remove hypochlorite, but its removal rate is slow. This process involves leaving water in an open container or bubbling air through it. A large, exposed water surface area is desirable for quicker dechlorination. As with boiling, hypochlorite is removed more quickly than chloramines. A day of aeration may be sufficient for hypochlorite removal whereas it may take days to remove chloramine from tap water with this method.

4.1.3 Metabisulfite

Metabisulfite (Campden Tablet) addition is effective for hypochlorite and chloramine removal. The tablets are either potassium metabisulfite or sodium metabisulfite. Both are effective in disinfectant removal. When sodium content in the brewing water is a concern, potassium metabisulfite may be preferred. Low potassium content in brewing water generally has less effect on brewing performance or taste. Adding these compounds at a rate of about 9 milligrams per liter (~35 milligrams per gallon or ~1 tablet per 20 gallons) or (~1 tablet per 75 liters) will dechlorinate typical municipal water and leave residual concentrations of about 3 ppm potassium or 2 ppm sodium (depending on the chemical used) and 8 ppm sulfate and 3 ppm chloride. These ion contributions are relatively insignificant and can be ignored in practice. The reaction equations for hypochlorite or chloramine with metabisulfite are shown below. Note that extra H+ protons are produced by the reactions (acidity) and the water alkalinity will be reduced.

4.1.4 Ascorbic Acid

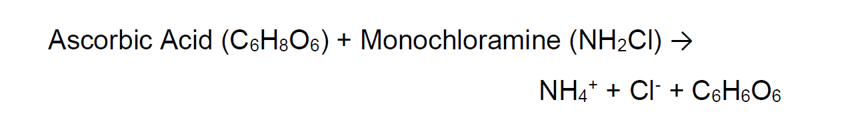

Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) addition is effective for hypochlorite and chloramine removal. As indicated in the compound's name, this is an acid and it does reduce water pH if unreacted with a chlorine compound. In distilled water, it can produce a pH as low as 3.0. It is sometimes used in municipal water treatment, however it's pH reduction effect and higher cost can make it less desirable than metabisulfite addition. Ascorbic acid is added at a rate of about 7.5 milligrams per liter (~28.4 milligrams per gallon) to remove up to 3 milligrams per liter of chloramine. The reaction equation for ascorbic acid and chloramine produces ammonium (NH4+), chloride, and dehydroascorbic acid. Since the dosing is very low, the resulting concentrations are not a concern. Be aware that ammonium is a yeast nutrient and is not a problem in brewing water. The reaction is shown below:

A similar dosage will also remove hypochlorite (OCl-) from water. The reaction produces water, chloride, and dehydroascorbic acid.

4.1.5 Activated Carbon Filtration

Activated Carbon Filtration of brewing water can be an effective disinfectant removal alternative. Activated Carbon is also known as: carbon, carbon block, granular carbon, or GAC. Both hypochlorite and chloramine are removed from the water by activated carbon while leaving most other water ion concentrations unchanged. While hypochlorite is easily removed with activated carbon, brewers should be aware that chloramine is removed from water VERY slowly and the use of activated carbon is not well suited to chloramine removal. Filtering with activated carbon can also remove water contaminants such as organic compounds that include taste and odor compounds.

Chlorine compounds are removed by activated carbon through an oxidation reaction with the carbon surface. The reactions for hypochlorite and chloramine removal are shown below.

The chlorine and contaminant removal performance of activated carbon filtration is proportional to the amount of time the water is in contact with the activated carbon. In addition, the volume of water that can be treated for chlorine compounds increases when the flow rate is low. Therefore, a low flow rate through an activated carbon filter is highly recommended to provide acceptable chlorine compound and contaminant removal performance and extend the life of the activated carbon media.

The design of an activated carbon filter system for chlorine compound removal is relatively simple. The residence time for water passing through the carbon media must meet certain minimum durations. For hypochlorite removal, the residence time should be at least 40 seconds. For chloramine removal, the residence time should be at least 6 minutes. Increasing these durations will improve the life of the media and increase the total volume of water that can be treated with the filter unit. (To provide an example of design recommendations for chloramine removal, kidney dialysis machine manufacturers typically recommend an 8-minute residence time for activated carbon, water pretreatment units) The residence time (also known as Empty Bed Contact Time) is calculated by dividing the volume of carbon media (say gallons or liters) by the flow rate (gal/min or L/min).

The flow rate through a standard under-sink (10-inch) activated carbon filter unit should be no greater than 1 gallon per minute to achieve good hypochlorite removal. Inserting a restrictor plate in the filter’s water supply line with a 1/16-inch diameter hole should reduce the flow rate through a filter to about 1 gallon per minute. The flow rate through smaller filters should be further reduced to provide adequate removal. The flow rate recommendation of 1 gallon per minute only applies for hypochlorite removal. Because of the reduced reactivity of chloramine with the carbon surface, the flow rate through a filter must be substantially reduced to provide adequate chloramine removal. A rate of less than 0.1 gallon per minute is likely needed when using a 10-inch filter unit. Since this very low flow rate may be impractical to most brewers, metabisulfite is recommended for chloramine removal instead of activated carbon filtration.

4.1.6 Testing

Hypochlorite and Chloramine removal can be verified through testing with swimming pool or aquarium test kits. If the water system does not use chloramine, then a readily-available "Free Chlorine" test kit will work well. If chloramine is used as the water’s disinfectant, then a slightly more expensive "Total Chlorine" or "Combined Chlorine" test kit is needed. Liquid test kits are recommended over test strips since they tend to be more sensitive at the low concentrations a brewer is interested in. Complete hypochlorite and chloramine removal is required since chlorophenols can be tasted at very low levels (~10 ppb).

4.2 Hardness Adjustment

Increasing water hardness is fairly easy. Gypsum (calcium sulfate), Calcium Chloride, Epsom Salt (magnesium sulfate), Magnesium Chloride, Chalk (calcium carbonate), or Pickling Lime (calcium hydroxide) additions can be used to increase the hardness. Reducing hardness is much more difficult. Options for reducing hardness are presented below:

4.2.1 Dilution

Dilution with distilled water or Reverse Osmosis (RO) water is a quick, yet more costly option. Distilled water is free of all ions while RO water is nearly free of ions. Both sources are very soft water that reduce the hardness and alkalinity of the brewing water in proportion to the amount of RO or distilled water added to tap water. The ion concentrations of these purified waters are typically lower than desired to promote good mashing, fermentation, and flavor results. Therefore, minerals should be added to these purified waters or the purified water should be blended with the original source water to provide an adequate ionic content for brewing use.

RO water is not pure water and it still contains low concentrations of ions. The concentration of ions in the RO water vary based on the ions and concentrations in the raw water entering the RO unit and the type of membrane used in the unit. To provide an indication of typical RO water quality, the following profile from a RO unit is presented as an example. The raw water feeding this RO unit came from an ion-exchange softener and that raw water had little calcium or magnesium, but relatively high sodium content. The sodium concentration in the treated RO water is slightly higher than if the raw water had not been previously softened.

The ion removal efficiency of RO units varies for each of the ions. The table above also includes the typical percentage of the raw water’s ion content that makes it through the membrane into the finished water (source: GE Water & Process Technologies). If the raw water quality is known, a rough estimate of the resulting RO water quality can be estimated using those membrane passage percentages.

Quality assurance of RO-treated water is an important component in maintaining brewing water quality. Since the RO process relies on a very thin membrane to purify water, any physical or chemical damage to the membrane could permit untreated raw water to pass the membrane into the treated water stream. A relatively simple and rapid test is to evaluate the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) of the RO-treated water. Inexpensive, portable TDS testing meters are available for this use. A TDS reading of about 20 ppm or less is typical for a properly operating RO system. If the TDS exceeds about 50 ppm, membrane replacement may be needed. This method of quality assurance testing is highly recommended when purchasing RO water from vending machines.

4.2.2 Decarbonation by Boiling

Decarbonation by Boiling is a practice that was employed historically and it does reduce alkalinity and calcium (hardness) in water with high Temporary Hardness. The boiling process drives off carbon dioxide (CO2) that helps keep chalk (CaCO3) soluble in water. When the CO2 is driven off, the chalk will precipitate out of the water. The process reduces only calcium and bicarbonate concentrations while leaving the water's other ion concentrations unchanged. Water with high Permanent Hardness cannot be treated effectively by this method.

The water is heated to boiling or near-boiling and stirred, splashed, or aerated to help get the CO2 out of the water. As CO2 leaves the water, chalk precipitates and causes the water to become cloudy. The heating is ended after about 15 minutes and the precipitate is allowed to settle quietly to the bottom of the vessel. When clear, the water is then immediately decanted off the sediment and used for brewing. The water cannot be allowed to sit too long on the sediment or CO2 will again diffuse from the atmosphere into the cooled water and redissolve the sedimented chalk.

This process does not reduce the magnesium content since magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) is much more soluble than chalk in water and the chalk precipitates first, leaving the magnesium with the remaining bicarbonate in the water.

Boiling reduces both bicarbonate (HCO3) and calcium content of the water when performed properly. The practical limit for the process reduces the bicarbonate content to between 60 and 80 ppm, although very good practices can reduce that to as little as 50 ppm. Therefore, the quantity of chalk that can be precipitated will be based on the difference between the starting and ending bicarbonate content. A reasonable assumption is to use an 80 ppm ending bicarbonate concentration since that allows for more error in the process. Alkalinity test kits can be used to assess the alkalinity reduction and the ending calcium content for the decarbonated water can be calculated using the following formula:

The equation above assumes that the water has a high enough calcium concentration to execute the reaction to volatilize the CO2 and precipitate the chalk. The practical lowest calcium concentration achievable through decarbonation is about 12 ppm. If the calculated calcium concentration is lower than 12 ppm when using the ending 80 ppm bicarbonate assumption, the ending bicarbonate concentration assumed in the equation must be increased until a 12 ppm calcium concentration is calculated. The Munich water profile is a case in point. Decarbonating that water to 80 ppm bicarbonate would leave only 7 ppm calcium in the water, which is below the practical limit. Therefore, the practical ending bicarbonate concentration must be increased to 95 ppm to leave the treated water with 12 ppm calcium.

A technique to help encourage and speed the precipitation of chalk from the boiled water is to add powdered chalk to the water. The undissolved chalk provides nucleation sites for the precipitating chalk to agglomerate with and form larger flocs that settle faster. A teaspoon of powdered chalk per 5 gallons (19L) mixed into the water should be sufficient to improve the settling. The added chalk does not dissolve and add to the water’s calcium concentration since it is not soluble in water without CO2. Use of gypsum to provide nucleation sites is less effective than using chalk.

Examples of the effect of Decarbonation by Boiling are presented in the water profiles below. The bicarbonate content was assumed to be reduced to 80 ppm for all the profiles (excepting Munich) and the precipitated calcium content was subtracted from the original calcium concentration. All other ion concentrations remain as for the original water. In the case of the Burton and Dortmund profiles, the low original RA and significant reduction in RA with boiling, indicates that those profiles do not need to be treated in this way for brewing. Typically, water profiles such as Dublin, Edinburgh, London, Munich, and Vienna are well suited to boiling treatment.

4.2.3 Lime Softening

Lime softening is another option for hardness reduction in water with high Temporary Hardness. This softening is typically conducted using either an Excess Lime or Split-Treatment process. These processes affect only the calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate concentrations while leaving the water's other ion concentrations unchanged.

When both calcium and magnesium concentration in tap water are excessive, the Excess Lime process is recommended. The Excess Lime procedure is recommended when the water's magnesium content is greater than about 15 ppm. In the Excess Lime process, pickling lime (calcium hydroxide) is added to the raw water to elevate its pH above 11. The high pH causes both calcium and magnesium compounds to precipitate out of the water. After the water clears, the water is immediately decanted off the sediment. When properly performed, Excess Lime softened water provides moderately-hard water with typical concentrations as low as 12 ppm calcium and 3 ppm magnesium in water with a high Temporary Hardness (low chloride and sulfate concentrations). When the water also contains significant Permanent Hardness (hardness associated with chloride and sulfate), lime softening is not as effective and the final calcium and magnesium concentrations will be higher than indicated here.

When the starting water has high Temporary Hardness and low magnesium concentration, the Excess Lime softening procedure above is modified to a Split-Treatment process that requires the pH be raised to only 10 instead of 11. This lower pH target still causes calcium to precipitate without affecting the magnesium content. The lower pH of the decanted water is easier to neutralize through aeration or acidification with this approach. When properly performed in water with a high Temporary Hardness (low chloride and sulfate concentrations), this process reduces calcium concentration to as low as 12 ppm calcium. The magnesium concentration is unchanged. When the water also contains significant Permanent Hardness (hardness associated with chloride and sulfate), lime softening is not as effective and the final calcium concentration will be higher than indicated here. Immediately after the water clears and the sediment has dropped, the water is decanted off the sediment. Since good brewing practice is to use brewing water with calcium concentration of at least 40 to 50 ppm, the Split-Treatment process includes blending a portion of the raw water with the decanted, lime-treated water to bring the calcium concentration back up to desirable level. This blending also reduces the high pH of the lime-treated water which makes it easier to bring the pH of the blended water down.

Since the water pH and alkalinity are high after treatment in either of the processes above, the pH and alkalinity must be reduced prior to brewing usage. Aeration (to dissolve CO2 in the water) and/or the addition of acid are suitable for reducing the pH and alkalinity of the decanted, lime-treated water. Reducing the pH of the lime-softened water to under 8.6 through aeration or acid addition is desirable. The lime-softening methods above require time, special chemicals, and a pH meter to perform successfully.

4.2.4 Ion-Exchange Softening

Ion-Exchange Softening is a common household water softening method that uses salt (sodium chloride or potassium chloride) to soften water. Water softened with this process should not typically be used for brewing water since the hardness ions (Ca and Mg) are replaced with elevated levels of sodium or potassium that may impart undesirable flavor and potentially harm the yeast. Since calcium and magnesium ions are beneficial to brewing, removing them from the water and replacing them with sodium or potassium is not desirable. Additionally, ion-exchange water softeners do not reduce the alkalinity of the softened water. Since the alkalinity remains high and hardness is reduced in softened water, the RA of the water is raised significantly, making it less suitable for brewing.

While the previous paragraph says not to use ion-exchange softened water for brewing, there are waters that may be ion-exchange softened and still be suitable for brewing. If the water has low hardness and suffers from elevated iron or manganese content, then that water may be acceptably treated with ion-exchange softening to help reduce the iron and manganese while avoiding excessive sodium or potassium content. The metallic perceptions from iron or manganese make the raw water unsuited for brewing. In general, if the sodium or potassium content of the softened water is below 50 ppm, it might be usable for brewing. Calcium can be added to the softened water to improve its brewing performance.

4.3 Alkalinity Adjustment

Alkalinity is the primary factor affecting the performance of the mash. Alkalinity is produced by bicarbonate, carbonate, and hydroxyl in the water. Bicarbonate is the predominant species in the typical municipal water system pH range of 6.5 to 8.5. There are several reasons why bicarbonate is the predominant species in tap water. Carbonate does not exist in significant concentration in that typical water pH range since it is preferentially transformed to bicarbonate. Hydroxyl is a strong base that reacts easily with impurities in the water. Since there are typically impurities in the water, hydroxyl does not exist in significant concentration in drinking water supplies.

Excessive alkalinity can reduce the quality and perception of pale colored beers. Alkalinity can also have a detrimental effect on beers made with Malt Extract since excessive alkalinity can drive up the pH of the reconstituted wort and finished beer. Water used for beers made with Malt Extract should have alkalinity under 50 ppm as CaCO3. The alkalinity of mashing water should be adjusted based on the acidity of the mash grist.

Most brewing requires that mashing water use low alkalinity water and all sparging water should have low alkalinity. Alkalinity can be reduced in a number of ways. Dilution with distilled water or RO water is effective in reducing alkalinity. Acid addition is also a simple way to neutralize alkalinity.

Brewing with acidic grists (significant roast and/or crystal malt content) can require that the mashing water have alkalinity. Alkalinity helps buffer the drop pH created by the acidic grist and helps keep the mash pH in the proper range. Chalk (calcium carbonate), Pickling Lime (calcium hydroxide), or Baking Soda (sodium bicarbonate) can be used to increase alkalinity. As mentioned above, sparging water should have low alkalinity and alkalinity-increasing minerals should not be added to sparging water.

A summary of alkalinity adjustment options are presented in the sections below.

4.3.1 Chalk

Chalk increases alkalinity. Because Chalk does not dissolve easily in plain water, chalk should only be added to the mash. Most acids in the mash are weak and only a small portion of the chalk will be dissolved. To fully dissolve chalk in water, it must be dissolved with an acid. In nature, CO2 forms carbonic acid in water which dissolves the chalk. Bubbling air or CO2 through a chalk water solution can be used to dissolve the chalk, but that requires time and effort.

Evidence has shown that even in the mash, chalk does not dissolve in significant quantity and the chalk’s theoretical amount of alkalinity is not produced in the mash. That evidence shows that the mash pH can only be increased by 0.1 to 0.2 units, no matter how high the chalk dosage is. Other brewing water references and software may assume either all or half of the theoretical alkalinity is added with chalk addition. A brewer should verify the assumption made by those resources for the amount of alkalinity added to the water from a chalk addition. A more comprehensive discussion on the time and pH dependent behavior of chalk is presented by AJ DeLange in the following link: http://wetnewf.org/pdfs/chalk.html (the website is currently non-functioning)

While chalk produces calcium and carbonate ions, the carbonate ions will eventually form bicarbonate ions in water with moderate to low pH. For a chalk addition of 1 gram per gallon, the effective bicarbonate concentration is increased by about 322 ppm assuming the chalk is fully dissolved. Undissolved chalk precipitates from the water and is not an active component of the water chemistry. In general, brewers should avoid using chalk for mashing water alkalinity adjustment since chalk is an unreliable alkalinity contributor. Other more reliable sources of alkalinity are presented below.

4.3.2 Pickling Lime

Pickling Lime (calcium hydroxide) increases alkalinity and is readily soluble in water, but must be handled with care since it can burn skin and eyes and significantly raise the mash pH if not dosed properly. Pickling Lime can often be found where home canning supplies are sold. It is also available at salt-water aquarium shops and may be found under the names: Kalkwasser, Lime, or Slaked Lime. Although pickling lime supplies hydroxyl ions to water, the hydroxyl content can be represented as a corresponding bicarbonate concentration for use in brewing calculations. For a pickling lime addition of 1 gram in a gallon of water, the corresponding increase in “effective” bicarbonate content is about 435 ppm and the calcium increase is about 143 ppm.

A problem with pickling lime is its purity. Pickling lime will degrade into chalk when exposed to moisture in the air. Therefore, pickling lime may not always produce the intended degree of alkalinity. The purity of pickling lime can be easily assessed by placing a drop of acid on a small amount of the dry powder. If the powder bubbles or fizzes, that is a sign that chalk is present in the sample. Pure pickling lime will react with the acid without bubbling or fizzing.

4.3.3 Baking Soda

Baking Soda increases alkalinity and is readily soluble in water, but its usage should be limited if the sodium content of the brewing water is a concern. Sodium at a concentration of 100 ppm or more may produce harshness in the beer flavor. Baking soda is relatively inert and does not degrade. Therefore, its strength (alkalinity) can typically be assumed to be consistent. A baking soda addition of 1 gram per gallon of water, increases the bicarbonate content of the water by about 192 ppm and the sodium content by about 72 ppm. Another way to look at baking soda's contribution is that when added to produce a moderate sodium increase of 40 ppm, the alkalinity of the water increases by over 85 ppm (as CaCO3). That alkalinity increase is often sufficient for brewing many dark beers.

4.3.4 Liquid Organic Acids

Liquid Organic Acids such as Lactic and Acetic Acid can be used for alkalinity reduction and acidification. Soured wort (sauergut) is a traditional German brewing method of producing dilute lactic acid for alkalinity reduction and acidification.

Lactic Acid is readily available for brewing use in many countries, but it can produce a distinctive “tang” in the flavor profile at high concentration. Lactic acid flavor is typically characterized as smooth. It is a weak acid that can be somewhat safer to handle than other stronger acids. Lactic acid is reported to have a flavor threshold of about 400 ppm in beer (Briggs et al., 1981). The flavor threshold can vary between tasters. Therefore, the 400 ppm threshold may not hold for all individuals. In addition, typical beers (especially German beers) naturally have a low concentration of lactic acid (typically 50 to 300 ppm) from malting, fermentation, sauergut usage, and production by-products (Briggs et al., 1981). Therefore, it may not be possible to use lactic acid to treat highly alkaline water without flavor impact. Lactic acid is a monoprotic acid and it consumes 1 part bicarbonate per one part lactic acid. For these reasons, it appears that the maximum alkalinity neutralization that lactic acid could provide for brewing is about 100 to 350 ppm reduction in bicarbonate (82 to 287 ppm alkalinity reduction, as CaCO3) in the water. In general, 1 ml of 88% lactic acid per gallon of water (0.37ml per liter) should avoid incurring lactic taste effects in brewing.

Lactic acid is quite stable and does not degrade appreciably when stored at room temperature in sealed containers. The shelf life of lactic acid stored at 80°C (176°F) is reported at over 80 years. However, lactic acid is hygroscopic and will absorb moisture from the air which decreases the acid’s concentration. Keep lactic acid in a sealed container to reduce air contact and loss of strength.